By: Margaret Jones

You probably have "that" friend – the one who can talk for hours about the subtle differences between subgenres of the same kind of music. Maybe you are that friend. As soon as you scratch the surface of any genre of music, you open yourself up to a slew of opinions about what categorizes a certain band into one bucket or the other, even if they pull influences widely.

Classical music faces the same conundrum. When many people think of classical music, they tend to think in broad strokes about orchestral, chamber, and operatic music. But what we consider “classical” music today covers over one thousand years of music, and in terms of how it sounds, who it was made for, and who plays it, it has a much richer and more diverse history than you might expect.

The earliest forms of what we consider classical music today began to form in the ninth century and became what is now known as Gregorian Chant; these tunes were the earliest ones written down. Over the following centuries composers built out that system, adding harmonies and eventually chords. While the system of notation held things together, depending on where, when, and why you were composing, the music wouldn't sound the same. A medieval song sounds vastly different from late Renaissance polyphony.

Beatriz de Dia (who composed sometime between 1175 and 1212) is one of the earliest female composers whose works survive. “A Chantar” is a troubadour song, written for entertainment at a royal court, and is the only of her songs to survive intact.

Thomas Tallis’ “Spem in Alium” (1570) was written as forty distinct parts for forty singers. Together, they create a wave of sound that ebbs and flows as singers enter and exit. It was written in part as an expression of the wealth and might of a young Queen Elizabeth I’s court.

The Baroque period (1580 to 1750…ish) features the work of European heavy hitters Johann Sebastian Bach, Antonio Vivaldi, George Frederic Handel, Alessandro Scarlatti, who helped codify opera. Structures took importance during this era; music was written in specific keys, and polyphonic music with multiple simultaneous melodies made for dense compositions.

Bach's BWV 1080 – played here by Cameron Carpenter – exemplifies a Baroque fugue, where multiple melodies intertwine and ultimately resolve.

The term "Classical" also refers to a specific period of time – roughly 1750 to 1820 -- encompassing the works of W. A. Mozart, Joseph Haydn, and the earlier works of Ludwig van Beethoven, among others. The style of the time was one of symmetry and proportion, building on some of the developments of the previous century to place virtuosic melodies over accompanying chord progressions.

After a few initial fanfares, listen to the violins in Mozart’s Symphony 41 in C Major, “Jupiter,” Movement 1 (1788). The melody twirls above the chords pulsating beneath in the rest of the orchestra.

A stylistic change started to set in around the first decade of the nineteenth century, however. Composers, especially Beethoven, began spinning entire symphonies out of rhythmic musical ideas instead of melodic ones, leading to the Romantic period of classical music, spanning roughly 1820 to 1900.

Jumping from 1788 to 1808, Beethoven creates an entire symphony movement out of the same “short-short-long” rhythmic pattern in his Symphony No. 5, Op. 67. Twenty years makes a big difference!

Over the course of the nineteenth century, some composers pursued a dramatic flair. Composers like Giuseppe Verdi and Richard Wagner wrote operas calling for elaborate sets and costumes that ultimately became inspiration for Silent- and Golden-Age-Hollywood producers and composers. Later in the twentieth century, avant-garde composers would push the limits of what orchestral instruments could play, incorporating denser harmonies and electronics with which live musicians would interact.

Olly Wilson (1937-2018) wrote the piece “Sometimes” for tenor singer and tape machine, using the tape to distort a mournful rendition of the African-American spiritual “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” inflecting it with disorientating percussive sounds and eerie string squeals.

With any genre of music, familiar or unfamiliar, you always will have more to explore, and making a genre too broad endangers understanding what makes each subdivision unique. With modern streaming services and well-curated record stores, it’s easier to narrow down genres within “classical” music, but it helps to know the breadth of what you’re diving into. As you listen to new music, ask yourself what it sounds like and what sets it apart. The closer you listen, the more you’ll hear.

Margaret Jones is a multi-instrumentalist, songwriter, and music teacher living in Oakland, CA. She plays guitar in several local bands including her own songwriting project M Jones and the Melee. She also holds a Ph.D. in Music History from UC Berkeley and has taught at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

”Sheet Music" by Ri Butov is licensed through Pixabay.

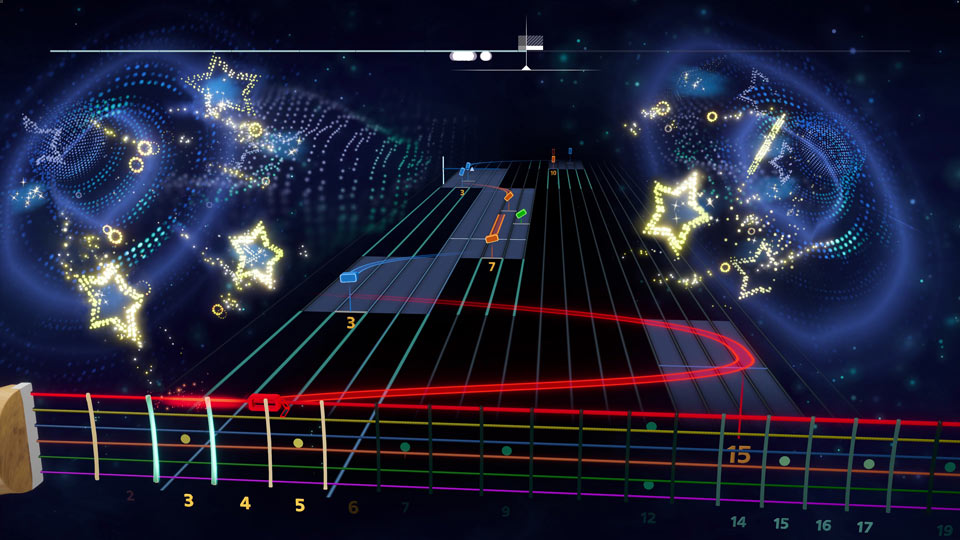

There's much more to explore with Rocksmith+. Click here and take the next step on your musical journey.