Imagine playing in an otherwise ordinary recording session when a piece of

studio equipment fails -- noisily and spectacularly. Then everyone agrees that

whatever other-worldly sound came out of the carnage needs to stay in the

recording because it made the song better! Fuzz, the elder statesman effect of

the guitar universe, began this way, and the modern world of guitar pedals is

forever indebted to that happy accident.

A broken transistor made for Grady Martin’s surprisingly gritty

bass solo in Marty Robbins’ “Don’t Worry.”

Fuzz is the sound of a signal gone wrong. Country songwriter Marty Robbins was

recording “Don’t Worry” at Bradley Film & Recording studios in 1960 when a transistor broke inside the

studio’s recording console. Bassist Grady Martin went on playing, capturing the

song’s signature buzzing bass solo. Howlin’ Wolf achieved a similar effect by

maxing out the volume of his amplifier on recordings like “Moanin’ at Midnight,” and Link Wray punched holes in the speaker cone of his amp to achieve the gritty tone on

“Rumble.” But destroying

equipment wouldn’t be sustainable long-term; musicians needed something more

reliable. Enter the fuzz pedal!

The Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz Tone was the first commercially available

stomp box. Originally marketed as a device to make guitars sound like other

instruments, it became a signature guitar sound of its own.

Audio engineer Glenn Snoddy developed the first fuzz circuit in 1961. Gibson

Electronics released it under the name “Maestro Fuzz Tone,” claiming the pedal

could mimic wind and string instruments. It was not until Keith Richards used it

on the main riff for “(I Can’t Get No)

Satisfaction” that the new sound really stuck. Several variations emerged in subsequent years, including the Sola Sound Tone Bender, the Electro Harmonix Big Muff, and the Arbiter Fuzz Face; early adopters of the pedals including Duane Allman, Jimi Hendrix, and George Harrison made their fuzz pedals integral to their sound.

Fuzz works by clipping the clean signal from your guitar, removing parts of

the sound wave to make it sound grittier. Unlike overdrive circuits, which

emulate the crunch a tube amplifier pushed to its limits, fuzz doesn’t “clean

up” at low volumes, and it adds additional harmonics (or, pitches above the

fretted note) to the sound. Sometimes it sounds chaotic and aggressive; other

times it sounds lush and complex. Compare the guitar parts in Miguel’s

“Hollywood Dreams” and Andrew Bird’s “Valleys of the Young.” One emphasizes the raw, messiness of fuzz guitar while the other slowly sweeps through the full – almost orchestral – harmonic range of the pedal. Same effect, just used two radically different ways.

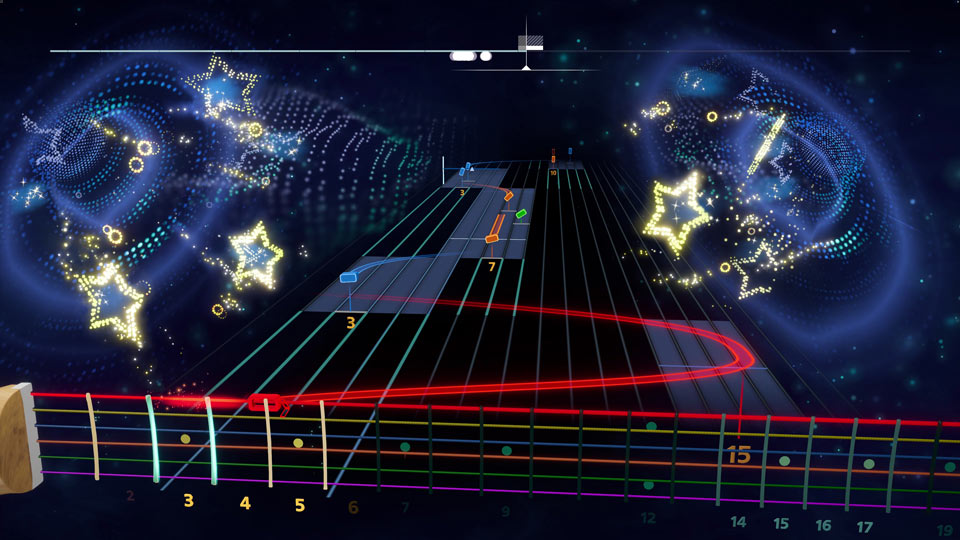

![[RS+] [News] What’s That Sound: Fuzz - fuzz zvex 960](http://staticctf.ubisoft.com/J3yJr34U2pZ2Ieem48Dwy9uqj5PNUQTn/7kNUWfcxh2yi62i5REbzDL/0cb622d106462322a4aa9993ede18805/fuzz_zvex_960.jpg)

Players recognize the Zvex Fuzz Factory by its distinctive horizontal

enclosure, hand-painted artwork, and completely bonkers sounds.

Many mainstream and boutique pedal companies have modified and innovated upon

these circuits over the years. The Zvex Fuzz Factory includes additional

circuitry that generates additional noises independent of the guitar; the Walrus

Janus uses joysticks in place of knobs to shape your sound. Depending on your

goals, you can find fuzz pedals that range from historically accurate to

outright chaos.

If you’re adding fuzz to your pedalboard, place the pedal first in your signal

chain, so your guitar's volume knob can sculpt the sound of the pedal. And if

you’ve only thought of fuzz as a messy, heavy effect, try imagining it in other

contexts and see where those sonic possibilities take you.

Margaret Jones is a multi-instrumentalist, songwriter, and music teacher living

in Oakland, CA. She plays guitar in several local bands including her own

songwriting project M Jones and the Melee. She also holds a Ph.D. in Music

History from UC Berkeley and has taught at the San Francisco Conservatory of

Music.

“black instrument

pedal” by

peakpx.com is licensed under CC0

1.0

"Zvex Fuzz

Factory" by

Art Bromage is licensed under

CC BY-SA 2.0

Learn to play this song and many more! Try Rocksmith+ yourself and take the next step on your musical journey.